Sandra Lipner is working on a historical research project into German-Jewish identity, family histories, and the Holocaust. As a History teacher originally from Germany, she was asked to talk to her students about her family’s history during the Nazi period. Hidden under decades of silence, she found Jewish roots, a history of assimilation, intermarriage and conversions, a grandfather in the Wehrmacht and a great-grandfather who steered the family and his business successfully through the Second World War. Her work on the family’s experiences during the First World War is due to be published by the city archive of Freiburg, and Sandra is starting a PhD looking at German-Jewish-Christian identities in the years 1871 – 1945 from September.

These views are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Wiener Holocaust Library.

Family history is often associated with dusty attics and antique shops, grandma’s stories and tomes of detailed local histories. However, recent publications about the Holocaust draw on family history in ways that are attracting the interest of historians and wider audiences beyond the local level.

Family History: Where Past and Present Connect

Historians have established beyond doubt that contemporaries living in Nazi-occupied Europe in the 1940s knew about the deportations of Jews and other groups deemed racially or ideologically undesirable to concentration and death camps. They agree that there was no knowledge gap and no post-war silence and that the many variations on the theme of ‘We didn’t know what happened to the Jews’ therefore constitute a popular myth. However, many individuals chose silence within their families as a coping strategy after the war in order to live despite what had happened. The wave of second and third-generation research currently being carried out and published is a response to the void this silence created and serves as a powerful reminder of how widespread this was.

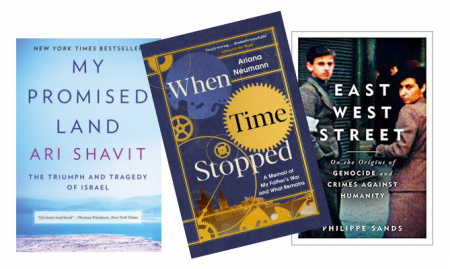

Published in March 2020, Ariana Neumann’s When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains traces her family’s history from life in pre-war Czechoslovakia, through Nazi occupation, war, the Holocaust and, for the few who survived, their lives beyond. The reason for her meticulously detailed research, and thus the hook for her book, was her father’s silence about what happened to him, his brother, their parents and relatives. ‘Sometimes you have to leave the past where it is – in the past’, was his firm belief to which he kept so resolutely that Neumann only knew he had migrated to Venezuela because the Second World War had wrought havoc with his country of birth.

Similarly, in his book East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity human rights lawyer Philippe Sands uncovers the answers to the unsolved riddles of his family’s wartime experiences. He pieces together the lives of his maternal grandparents in order to learn about their history, which they never shared with him. All he knew during their lifetimes was that they were Jews from Lemberg and Vienna and that Sands’s grandfather and mother migrated to Paris in 1939 whilst his grandmother stayed behind. To explain the effect this had on him, Sands quotes Nicholas Abraham, ‘what haunts are not the dead, but the gaps left within us by the secrets of others’.

The same post-Holocaust silence features in Ari Shavit’s history of Israel, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel. Drawing on family history (his own and that of others), Shavit discusses ideas and persons that shaped Zionism from the late 19th century until 2013 and investigates how Zionism fitted – or did not fit – into the wider historical and geopolitical context of the Middle East. He observes that the post-Holocaust silence in families was so pervasive in Israel in its early years that its effects were palpable across Israeli society. Shavit is of the opinion that ‘to survive, people cleanse themselves of the past; to function, they flatten themselves’. A person with a flattened identity in Shavit’s sense functions but lacks depth, much like a photograph resembles real life but is two-, not three-dimensional. A flattened identity is not organically connected to the past. Shavit’s metaphor is a useful way of thinking about the current wave of family history publications by second- and third-generation authors. By engaging in the creative process of researching and writing their family histories, they connect with the past and revive any parts of their own identities that remain flattened by the unexplained voids of their families’ experiences.

Looking In & Looking Out: The Insider-Outsider Perspective

Neumann, Sands and Shavit write from the inside out by drawing on their intimate knowledge of their families and from the outside in when filling in the gaps in their knowledge of what happened. Neumann is fully aware of the poor reputation of this perspective as “just another unreliable witness telling a story as I wanted to hear it.” She overcomes this convincingly by authenticating every detail contained in her father’s box of papers and following every link about all related people, places, and companies. Working on an even larger scale that includes multiple narrative strands beyond his family, Sands is a keen enthusiast for verifying his evidence and connects dates, people, and events across continents and decades much like a detective. Thanks to his minute attention to detail he is able to point out, for example, that the publication of a Baedeker travel guide for the General Government commissioned by Hans Frank, the Governor-General of occupied Poland, coincided with his indictment as a war criminal responsible for 400 000 deaths by the Polish government in exile, thus linking Frank to the tragic histories of Lemberg and Sands’s own family. By including the lives of powerful people and brilliant legal minds of the time in his family’s history, Sands emphasises his outsider’s perspective and embeds his family’s history within a larger work of history and a study of international law.

Shavit’s work is similar to Sands’s in scale and methodological approach in that he maps the actions of individuals across space and time. He writes from the centre of the events he chooses to cover and makes every effort to understand deeply even those aspects of Israel’s history that appear alien to him. He gets inside the early period of the Zionist project, for example, by connecting with his British great-grandfather’s Zionist pilgrimage in 1897, then investigates key places of Israel’s and his own curriculum vitae. Shavit roams the whole of Israel to find people and places relevant to his book and thus uses a similar technique to Neumann and Sands in that he presents the country and the positions of the different protagonists through the prism of his own views. Aware of this, he reflects openly on his politics and ideological outlook and thus gives the reader an insight into Israel’s complex political spectrum across time. Despite the criticisms levelled at him from left and right for his liberal Zionist stance in the context of a deeply conflictual situation, his audience stands to gain much from Shavit’s approach and analysis.

All three books use family history to shed new light on the Holocaust and other historical events. By offering vivid mosaics of biographical stories taken from family history and beyond, they contribute deep layers of meaning to the histories they touch. The revelation of new and profoundly relatable material within a setting of such severe threat as the Holocaust makes these books read like detective novels or first-rate thrillers. Far from being works of fiction though, they have the capacity to contribute valuable evidence to the general historical record because of the authors’ commitment to historical accuracy and reliability.

Suggested further reading:

- House of Glass: The story and secrets of a twentieth-century Jewish family by Hadley Freeman

- I Want You To Know We’re Still Here: My family, the Holocaust and my search for the truth by Esther Safran Foer

The Wiener Holocaust Library holds a number of books and documents relating to this subject, some of which are listed below:

- My Dear Ones: One Family and the Final Solution by Jonathan Wittenberg

- The Missing: The True Story of a Family in World War II by Michael Rosen

- Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spiegelman

- When Memory Comes by Saul Friedlander

- Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind by Sarah Wildman

- Survivor Café: The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory by Elizabeth Rosner

- The Cut Out Girl: A story of war and family, lost and found by Bart Van Es

- The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance by Edmund de Waal

- Sing this at my funeral: A memoir of fathers and sons by David Slucki

- What you did not tell: A Russian Past and the Journey Home by Mark Mazower

For more related sources, try a search for any of the following keywords in our Collections Catalogue: Personal narratives, Second/Third generation, Survivors, Jewish history, Biographies, Refugees, History.