Staff of the Library consider the ethics and practice of Holocaust-era artefact reproduction

Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

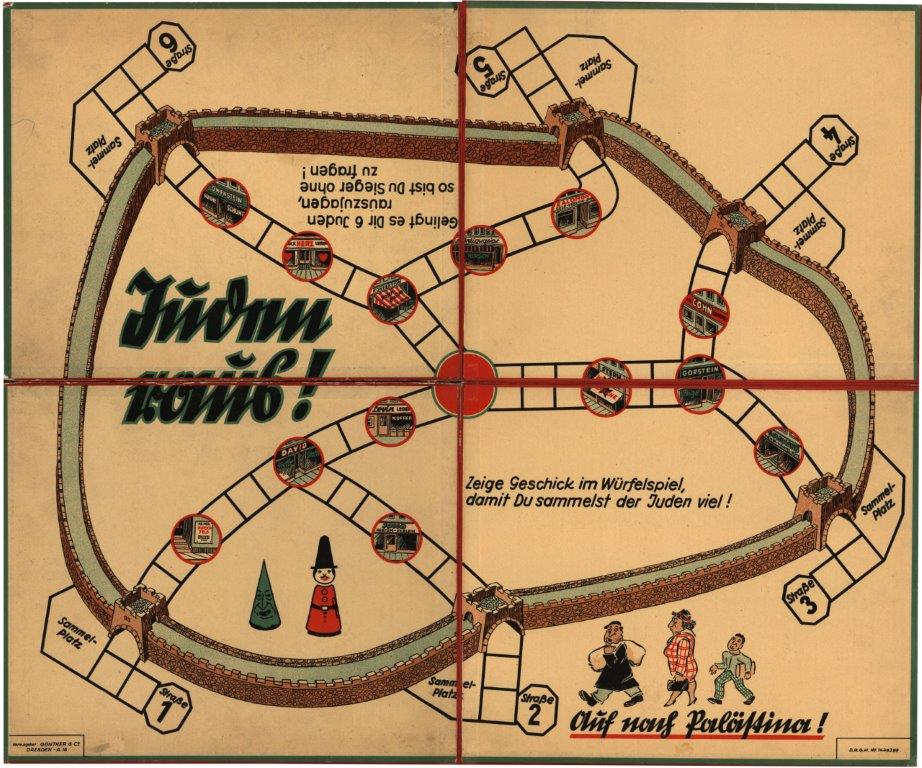

Recently, an institution approached The Wiener Holocaust Library to enquire if they could create a replica of one of the artefacts in our collection for display in their upcoming exhibition. The item in question is the Juden Raus! board game, which uses crude antisemitic stereotypes to implement an “outstandingly jolly party game for adults and children”.[1] Although not endorsed by the Nazi party, the game and its imagery demonstrate broad racial hatred, forced deportations, and confiscation of Jewish property – a reflection of the 1930s German societal and cultural environment in which the game was created.

The proposal sparked a lengthy discussion about the ethics of reproduction and purposes of replicas of Holocaust-related artefacts. The conversation revealed diverse reactions to the request and raised a variety of aspects to consider from collections management, archival and museum ethics, to curatorial practice and museum education, both more broadly and specifically related to atrocity and Holocaust exhibition and collections management.

Currently, all Library staff are working from home, and therefore, we’ve had some time to reflect on our practice and the broader implications and meaning of what we do. Below we share two perspectives from Greg Toth, Head of Collections, and Dr Christine Schmidt, Deputy Director and Head of Research.

Greg Toth, Head of Collections:

Archivists and librarians have long debated the purpose of collecting. Meanwhile some focus on safekeeping items, others campaign for broad access. The former wrap materials up and put them in vaults, the latter prefer to put everything into the hands of researchers. To strike a balance between preservation and access can be tough. Somehow a careful middle way must be discovered. No one would disagree with me that it is an acceptable process to create digital copies of a fragile printed document, or photographs, for the sake of perpetuation. But should it be the same with 3D items?

Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Creating surrogates happens for various reasons at heritage institutions. It can be for improving access: e.g., not everybody is able to physically visit archives and libraries and as a reason a large number of holdings are regularly being scanned and digitised to make them freely available online. It can also happen for preservation reasons: e.g,. some items are fragile, or in poor condition, and thus need extra safekeeping. By creating digital copies, archivists and librarians proactively protect items simply because they are less touched and handled. Both approaches serve the need of prolonging the life of items for future generations. And I am not thinking about protection for the next decade but even longer: for the next 250 years. The core aim of any surrogate creation is to make sure that original materials will be here as testimonies of their time long after we are gone. Following Alfred Wiener’s steps, we should continue safeguarding the Library’s rare and unique collections as much as Wiener himself, and previous custodians, did. I often think of all those librarians and archivists who carefully looked after, for example, the Magna Carta or the Domesday Book. I would like to believe that they were thinking of us when they struggled as much as they could to save those national treasures.

Providing access to all our holdings is one of the Library’s core missions but making sure that our documents last and are available to future generations is another one. One way to achieve a balanced approach is to seek all opportunities to reduce the risk of damage to our items. This can include a set of activities while making as few changes as possible. For example, continuously monitoring conditions of items, maintaining the temperature and humidity in collection storage areas, writing a plan in case of emergencies, monitoring pests, assessing security, implementing supports and aids, and many more.

But in some cases, and it might be the right one with the Juden Raus! game, it means producing a replica copy and only showing the original on special occasions. This is because, apart from one other institution in Israel, The Wiener Holocaust Library is the only institution which has two full sets of the game. Consequently, there is a huge demand for the game and one copy is constantly on loan to external institutions. The Library receives 6-8 requests per year and many of these requests desire the game for long-term exhibitions. However, every time the game is packed, travelled, unpacked, and displayed, and affected by handling and light exposure, its condition deteriorates. Although in the short term, this minor damage might not be visible to the human eye, in terms of decades, or even centuries, it suddenly does matter.

If the Library had a replica copy, we might offer to loan that copy instead of the original. We might only display the original version once a year for a short time only or on special occasions. Will there be an issue of showcasing replicas of our items in exhibitions? I believe when we visit museums like the British Museum and look at Greek statues, we never really have the same concern. Many Greek statues survived only because Roman artists copied them. Although the Greek statues are long gone, their Roman copies are admired by millions today.[2] I do acknowledge that it is not exactly the same argument but perhaps an interesting point to consider.

At the end of the day, we are trying to position the Library where access to our original holdings is provided for as long as possible. And if it means showing replica copies rather than the original one, that’s a sacrifice I believe the Library should make.

Christine Schmidt, Deputy Director and Head of Research:

The proposal to create a high spec, exact replica of the Juden Raus! game raised a number of thorny issues for us. One of the arguments made for the replica was preservation, as Greg has ably outlined here. Yet another was for the purposes of education and exhibition display: although the Nazis themselves didn’t promote the game, with the SS publishing a rather disparaging review of it in Das Schwarze Korps, decrying the crass attempt by Rudolf Fabricius, the game’s distributor, to capitalise on the serious ‘issue’ with which they were contending (the ‘problem’ of the Jews), the game is among the most sought after and well-known objects in the Library’s collection.[3] In addition to the number of annual loan requests, it was shown as part of the New York Museum of Jewish Heritage’s permanent exhibition for years, and most recently, in the inaugural version of the hugely popular Musealia-curated Auschwitz: Not Long Ago, Not Far Away exhibition in Madrid.[4] Therefore, the replica proposal seemed worthy of our consideration.

The discussion revealed a number of critical hesitancies, many of which have been traditionally considered and debated within the museum and heritage fields in a variety of contexts, not solely related to the display of atrocity and Holocaust-era artefacts. For example, is it ethical to enter into and embrace the chemical, mechanical and artistic process of replicating an object that had such vile implications and uses, and which was originally created with the intention of tapping into and promulgating racist views? Does the need for this object as an educational ‘tool’ outweigh the ethics of aesthetic recreation? To what extent does a replica convey the same sort of meaning as the ‘authentic’ object to exhibition visitors, that ‘sacred aura’ that often captures the imagination and emotionally moves a visitor?[5] And in the case of Holocaust-era artefacts, is it advisable to produce replicas for education when one of the stated justifications for Holocaust education is to combat denial – wouldn’t ‘a fake’ object undermine these efforts?

We also discussed decay, and that objects related to the murder of millions (the game being a relic of precursors to genocide) ought to be left to rot and disappear. An article in the Pacific Standard about the theft and subsequent reproduction of the Arbeit Macht Frei gate at the Auschwitz Museum grappled with this question: “As time erodes the ephemera of genocide, the purpose behind preserving every physical bit of atrocity becomes a question for archivists and ethicists.”[6] These are not new debates and are reminiscent of the controversies surrounding the display of replica boxcars as well as on the preservation of sites of murder more generally.

What was most interesting to me, however, is that our discussion revealed something about the changing perceptions of the significance of the game as an object of material culture from the Nazi period. To what extent does the game demonstrate the pervasiveness of antisemitic views? Is that where its significance as an object lies? If it was, as Das Schwarze Korps contended, an attempt to cash in on the prevailing mood of the country, isn’t it then logical to deduce that the game reflected antisemitic attitudes in Nazi Germany as revealed by this cultural marker, geared toward banal family fun? One might assume that if this was the case, the game would have sold well; but in fact it may not have been a commercial success, perhaps in part because of the SS’s negative review.[7]

Yet, considering the number of requests we have to display the game, our discussion revealed many dimensions about the biography of this object and the multiple layers of meaning that have been attributed to it since the end of the Second World War. Although perhaps its significance at the time was minimal, it is clear that for the Library and its visitors, as well as other museum and heritage institutions, the game carries import. It’s probably a stretch to claim that, in the words of Oren Stier, it has reached ‘iconic’ status, but perhaps amongst our own collections it has.[8] For example, in moving to our current premises at Russell Square in 2011, a special, moveable display case was created expressly for the game. (We regularly repurpose the case for our other exhibitions now). The game is often displayed for tours and guided talks, including visits by donors. It was featured on the special episode of the BBC-produced Antiques Roadshow for Holocaust Memorial Day 2017. In some ways, the game has become synonymous with the Library and its foundational collections: the Library was built on examples of Nazi propaganda and antisemitic tracts collected by Alfred Wiener and his colleagues as they were being disseminated and to serve as a warning. Juden Raus! is not the only racist game, nor is it the only game we have in our collections, but when we refer to ‘The Game’ among the staff, we know which one we mean.

What then is the significance of this object, warranting the production of a replica? Arguably, the place of the object among the Library’s collections and among sister institutions’ exhibition displays confer deeper meaning, and its placements have attributed additional biographical layers. This, coupled with its sheer ordinariness as a vehicle for antisemitism, perhaps tell us just as much (if not more) about us, about current Holocaust memorial culture and education, as the Nazi period in which it was created.

Works cited:

[1] Juden Raus! Rulebook. In German: “Das zeitgemässe und überaus lustige Gesellschaftsspiel für Erwachsene und Kinder”. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

[2] On the uses and significance of replicas of archaeological material, see Sally Foster and Neil Curtis, “The Thing about Replicas—Why Historical Replicas Matter”, European Journal of Archaeology 19 (1) (2016): 122-148.

[3] Andrew Morris-Friedman and Ulrich Schädler, “Juden Raus! (Jews Out!) – History’s most infamous board game”, Board Game Studies 6 (2003): 47-58.

[4] Currently, this exhibition is on display at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, though the game has been returned to the Library for conservation.

[5] Oren Baruch Stier, Holocaust Icons: Symbolizing the Shoah in History and Memory (2015): “This symbolic expression is enhanced by the emplacement of these artifacts in specific memorial environments, which, in turn, sometimes exude a sacred aura” (37).

[6] Michael Scott Moore, “The Awkward Case for Preserving Holocaust Relics”, Pacific Standard, 30 December 2009.

[7] Morris-Friedman and Schädler, 56.

[8] Stier writes that “Objects become icons when they have not only material force but also symbolic power” (7).

Suggested Further Reading:

The Wiener Holocaust Library holds many books and documents relating to antisemitism during the Nazi period. For more related sources, try a search for any of the following keywords in our Collections Catalogue: Games; Antisemitism and Indoctrination.

One comment so far

I was one of the co-authors of the paper on this game. I created a copy to use in my lectures on the history of board games, using a color photocopy of the game board and replica pieces. I have never seen a picture of the box the game came in. Often in board games the art work of the game box is more interesting/revealing than the objects that make up the game itself. I would be very interested to know if any of the game box covers exist.