Supported by funding from Arts Council England, the Wiener Holocaust Library was able to undertake cataloguing and digitisation of three exceptionally rich and extensive collections of family papers in order to make them available in perpetuity for researchers. The third of these, the Ernst Levy Collection, spans 19 boxes of documents and photographs and pertains to the Levys, an assimilated Jewish family from Berlin, whose survivors became refugees from Nazism.

The oldest of three children of Alfons and Flora Levy, Ernst Moritz Levy (1894-1982) grew up in an affluent middle-class household. Upon receiving his PhD, the trained lawyer became a partner in his father’s successful timber sales business in the mid-1920s — a sector he would continue to work in his entire career. On a business trip to Switzerland, he met his future wife Helen Thilo, an English born German foreign language secretary. In the wake of his father’s passing and the ‘aryanisation’ of the company, Ernst emigrated from Nazi-Germany in summer 1938 and settled with Helen in London. The couple would have two children

Like for so many of his generation, fighting in the First World War had been a formative experience for young Ernst. Having started his military service the previous year, he was on active duty from 1914 to 1918. An avid amateur photographer, he widely captured his deployments to both the Eastern and Western front. Some 1,400 photographs from this period depict various scenes related to the military service of a young German Jew in the Imperial Army for which he was promoted Lieutenant and awarded the Iron Cross.

Twenty years later, the country he had fought for so bravely would leave him no choice but to emigrate. Just in time, as preserved correspondence with his mother indicates. Describing the hardships of everyday life, her letters allow insights into the dramatic situation of the remaining Jews in Nazi-Germany 1938/39. ‘It is so devastating that our situation can hardly be described’, she wrote, for example, a few days after the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht), ‘we are so frightened that we hardly dare to even speak about our pain.’ With the help of her son, Flora Levy was able to move to the UK eventually.

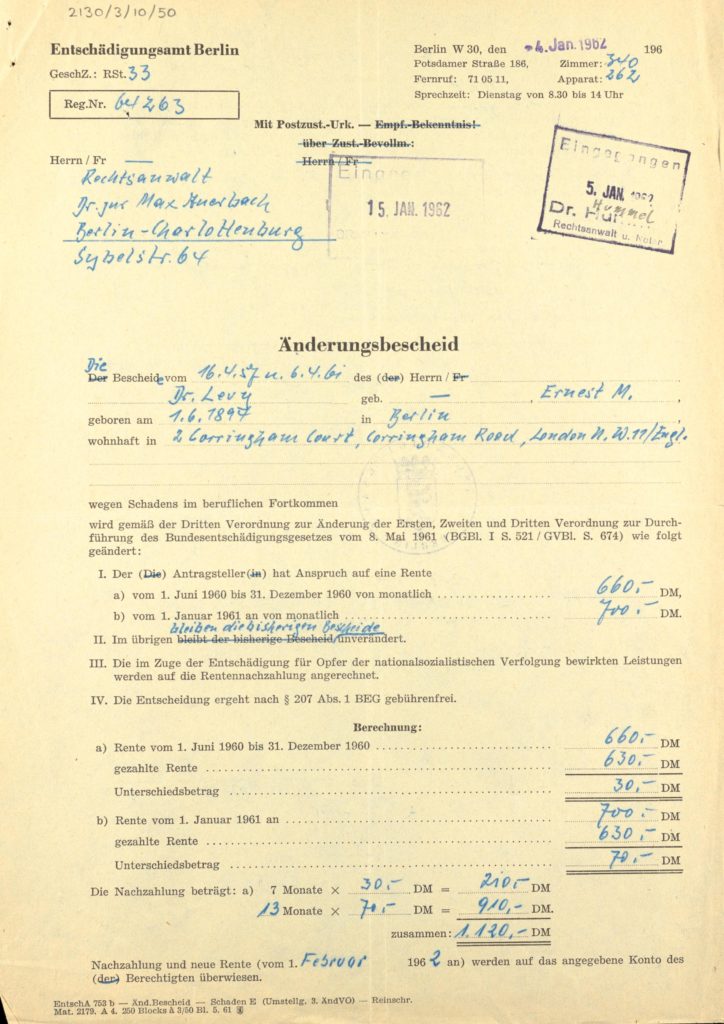

Aside from an internment as ‘enemy alien’ by the British authorities from 1940 to 1941, Ernst succeeded in settling smoothly in his country of refuge both privately and professionally. His focus, however, remained on is immediate and extended family which he supported tirelessly over the years. After the end of the Second World War, he took up the painful task of tracing relatives murdered in the Holocaust, and would assist others from his now scattered family with restitution and estate matters. A copious amount of related correspondence in this collection sheds light on some of the obstacles survivors had to overcome when asserting their rightful claims.

Upon retirement, Ernst also devoted his time to keeping parts of the family archive.