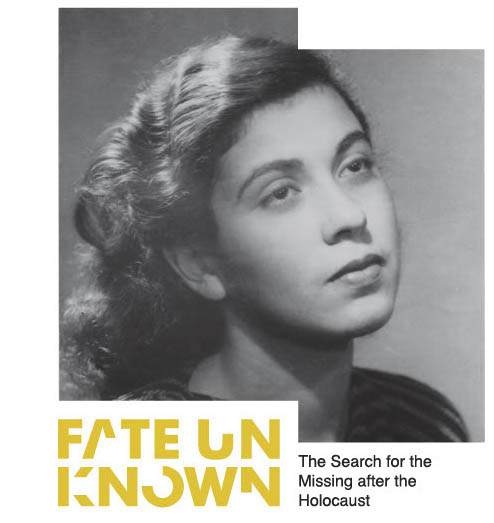

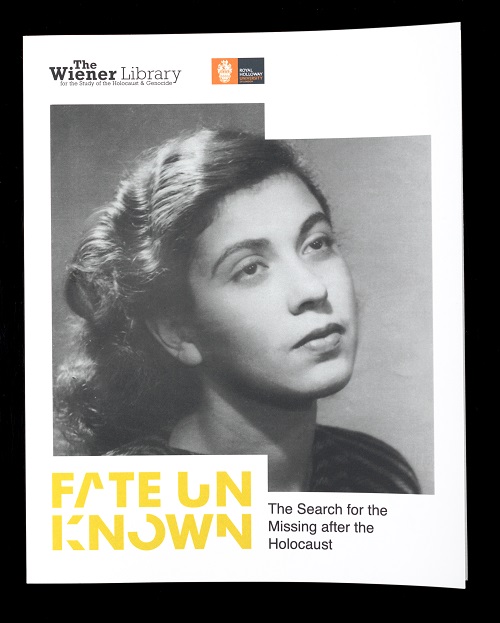

Zuzana Knobloch (née Hartmann), missing since September 1943. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections. Introduction

By 1945, Europe was in chaos. Millions of people had been murdered or displaced by war and genocide. Many were missing, with the fates of some remaining undetermined more than seventy years later.

The Allies tried to cope with the war’s aftermath, including masses of people on the move. For many Holocaust survivors, the possibility of finding loved ones was a primal need and took precedence over everything else.

Different charities and agencies, such as the British Red Cross Society, attempted to help find the missing. Their efforts came together as the International Tracing Service (ITS).

This online exhibition examines the complicated history of the search for the missing after the Holocaust and the impact today of fates that remain unknown.

Missing since September 1943, Zuzana Knobloch, a young Czech Jew, was arrested in Prague with her husband, Ferdinand, for resistance activities. Zuzana’s parents were murdered after being deported from Theresienstadt in 1942. It took her surviving family many decades to uncover her likely fate. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

A postwar Czech index revealed that Zuzana Knobloch had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on 25 November 1943. It is presumed that she died there. ITS Digital Archive 4999265. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Liberation?

At war’s end, millions of people were somewhere other than where they wanted to be.

For Jewish survivors, especially those from Eastern Europe, the future was uncertain. The search for family members and friends drove many to return home, even in defiance of military efforts to control the movement of people. When some did reach home, they found their communities destroyed and family missing. They often faced hostility and violence.

“I almost despaired at the seemingly endless difficulties; information written on dreadful old scraps of paper in a dozen languages…. Thousands of people wanted to know whether we had found any trace of this or that missing relative or friend.”

Evelyn Bark CMG OBE, British Red CrossThe Aftermath

Allied militaries faced daunting challenges. They needed to aid Displaced Persons (DPs) and help relieve disease and hunger. They aimed to regulate the movement of people so that military operations could continue. They tried to repatriate as many people as possible.

For a time, these goals were prioritized over finding missing people and reuniting families, even though military forces received many requests to find the missing.

Several charities and organizations tried to help within post-war occupied Europe and beyond. With no central authority in place, relatives approached as many organisations as possible with information about the last known whereabouts of family members.a

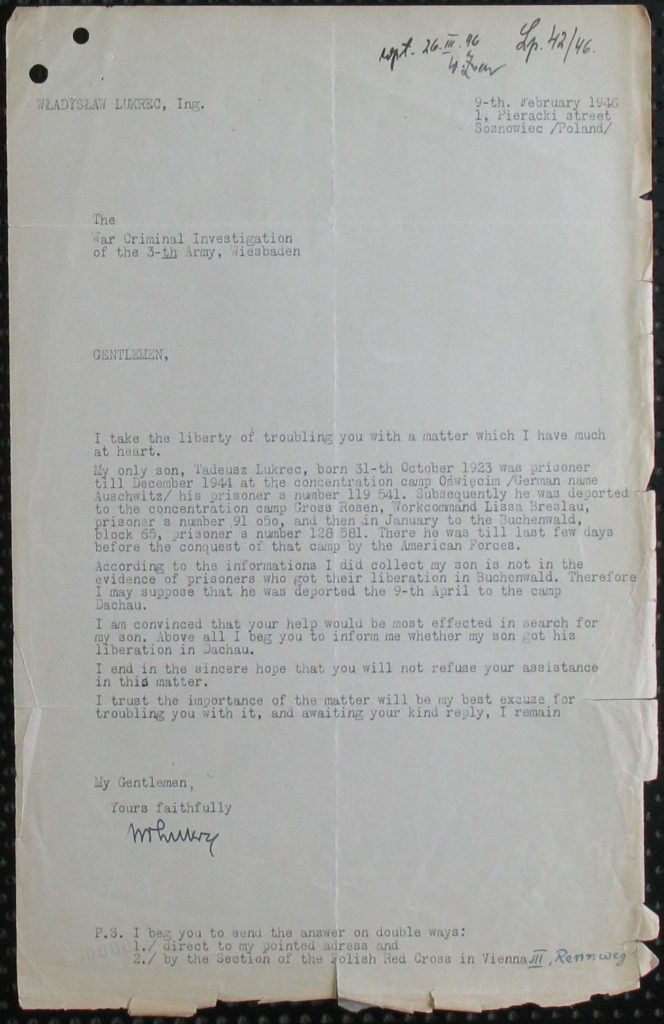

Władysław Lukrec launched a search for his son, Tadeusz, on 9 February 1946, writing to as many organisations as he could. Taduesz had been imprisoned in Auschwitz, Gross-Rosen, and Buchenwald camps, and Władysław desperately sought his whereabouts. Documents in the International Tracing Service archive do not reveal whether father and son were reunited. ITS Digital Archive, 90583911. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Even before the liberation of Bergen-Belsen camp, inmates compiled lists of survivors. After the liberation, these lists formed the basis of tracing work in the Displaced Persons camp set up there. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), the British Red Cross, the Jewish Relief Unit, and the American Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) helped administer the DP camp. The retreating Germans had destroyed most of the camp’s records. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

The search for family members was global. This Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) advertisement was published in a German Jewish refugee newspaper in Shanghai. The German text reads: ‘HIAS (HICEM) representatives in all parts of the world search for relatives in all countries of the world. Individual help in searching for relatives. Collective telegrams, information about further emigration. Reliable information about immigration requirements as well as living conditions in overseas countries.’ c. 1945-48, United States Holocaust Musuem, courtesy Ralph Harpuder.

This advertisement was placed by Sara and Irena Ceder in Tel Aviv in a Yiddish newspaper in New York. They were searching for their aunt and uncle, Franya and Filip Klein. c. 1950, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

German and Austrian Jewish refugees who had come to England before the war wrote to a variety of agencies to learn about the fates of relatives who remained on the Continent. Berta Fraustaedter’s children, Lotte, Kurt and Hans, had fled Nazi Germany. With the assistance of the British Red Cross Society and the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, among others, they learned that their mother, Berta, had survived the Theresienstadt ghetto. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Berta’s name appeared on a list of Berliners published by the World Jewish Congress in the Aufbau, a journal for German-speaking Jews founded in 1934. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

As early as 1943, a number of organisations in the UK met to discuss the creation of a centralized Search Bureau. Chaired by Otto Schiff, who supported Jewish refugees who came to Britain, the organisations included the Quakers, the British Red Cross Society, Association of Jewish Refugees and the Women’s Voluntary Services. This report for June 1944 – April 1946 was prepared to document the efforts of the UK Search Bureau. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

The Welt im Film

The Welt im Film [World in Film] newsreel series was produced by the American and British military governments to support the postwar denazification campaign in Germany and Austria. This clip shows footage of the Central Tracing Bureau at work.

Organising Chaos

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) seemed to be the natural agency to take responsibility for tracing after the war. However, its ‘neutral humanitarianism’ was at odds with the Allies’ insistence that the Central Tracing Bureau would not deal with German POWs or civilians – this would be the task of the German Red Cross. The Allies also prioritized repatriating Displaced Persons, which was officially outside of the ICRC’s remit.

© British Red Cross Museum and ArchivesInternational cooperation among charities and other bodies was key to facilitating tracing efforts. Some Displaced Persons arranged search organisations and compiled lists of survivors. Relief organisations, such as the Jewish Relief Unit, tried to help. authorities recognised the need to centralise search efforts, which often duplicated activities or worked at cross purposes.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) seemed to be the natural agency to take responsibility for tracing after the war. However, its ‘neutral humanitarianism’ was at odds with the Allies’ insistence that the Central Tracing Bureau would not deal with German POWs or civilians – this would be the task of the German Red Cross. The Allies prioritised repatriating Displaced Persons, which was officially outside of the ICRC’s remit.

Administration of the International Tracing Service

The Central Tracing Bureau (in 1948, renamed the International Tracing Service) had been administered by different institutions since the end of the war. In 2012, the ICRC resigned from managing the ITS, because the ITS had expanded from processing tracing requests to include opening its archives for research, education and commemoration. The German Federal archives is the institutional partner of the ITS. The ITS is overseen by an International Commission, including representatives of the United Kingdom.

Moving Towards Centralisation

After the war, military authorities aimed to control searching to regulate the movement of refugees. They also wanted to track and limit information that was being shared across borders. The Cold War was developing. The Soviet Union withdrew its cooperation in central tracing when it realised Soviet citizens were permitted to resettle in western countries on political grounds.

The Central Tracing Bureau (CTB) coordinated initiatives among national and zonal tracing offices by July 1945. The CTB was the predecessor to the International Tracing Service. Lists compiled by various charities and organisations were gathered by the CTB and used in its tracing work.

The Search Bureau for Missing Relatives was created in 1945 by the Jewish Agency for Palestine to help relatives find each other. It published lists of names in a weekly bulletin called To the Near and Far and broadcast names over the radio. 1956. Central Zionist Archives.

Initially, the Allies envisaged a situation whereby each Allied nation would establish its own National Tracing Bureau (NTB) and the Central Tracing Bureau would act as a ‘clearing house’ for cases which they could not solve, or which required the cooperation of several NTBs. UN Archives.

In January 1946, centralised tracing was moved from near Frankfurt to Arolsen, Germany, which was more or less undamaged at the end of the war. Thirty miles west of Kassel, it was close to the borders of the US, British and Soviet occupation zones. It had been a Nazi stronghold during the war, and initially, a former SS barracks was used to store documentation for tracing. Arolsen Archives.

While fielding tracing requests, the Central Tracing Bureau indexed the documents that were being collected for names. It also incorporated name cards that had been created by other agencies. The Master Index, known today as the Central Names Index, includes records of enquiries, summaries of search files, and references to documents.

© International Tracing Service, Cornelis GollhardtGathering the Names

Tracing bureaus collected documentation related to the last known whereabouts of individuals. Evidence not destroyed by the Germans, such as documents from concentration camps, hospitals and factories, was repurposed for tracing work. To this were added Displaced Persons’ registration records and census lists compiled by different organisations, like the World Jewish Congress. Mass broadcasts over radio issued immediately after the war were another method for locating people.

Overcoming Obstacles

Surviving documents were not always accurate or complete. Many victims and survivors shared the same name or spelt their name in numerous variations. Moreover, many had given false names and ages upon entering the camps or to liberating authorities.

Collecting documentation and facilitating searches in the field were two major logistical challenges. After the zonal offices were dissolved in the early 1950s, the focus shifted to searching for individuals based on the documents collected.

Multiple languages were needed to process requests for information. Often Displaced Persons were employed to help facilitate requests. Hoechst, Germany, c. 1944-48. UN Archives.

Here, incoming mail is sorted to language and country, in preparation for the search for the missing person. Hoechst, Germany, c. 1944-48. UN Archives.

Case Study #1: Gita Esther Nussbaum

Courtesy Maurice Smith. Gita Nussbaum was born in Liepãja (then Libau), Latvia on 2 March 1933. From about 1936, she was in the care of her aunt and uncle, Sophie and Noah Heiden, in Liepãja. After the war, her parents, who had survived with her older sister in Corsica, searched for her.

Her fate remains unknown.

Identifying the Unknown Dead

An American soldier studies a grave marker on the sight of a mass grave of death march victims.

c.1945 © USHMM, courtesy of Joseph EatonThe Allied authorities issued an order in October 1945 to all mayors across Germany ‘to discover, register and eventually concentrate into separate national cemeteries, all Allied graves’.

Fieldworkers set out to check graves and retrace the steps of concentration camp inmates who had been sent on forced marches (often called death marches).

Graves Recheck

Fieldworkers compiled summaries and hand-drawn maps identifying the location of ‘unknown dead’ and grave sites. They collected witness statements from those who saw the ‘death marches’. These investigations continued until 1951.

The investigations formed part of the materials the CTB (later, the International Tracing Service) used to trace missing persons.

Establishing the death of an individual had legal repercussions. Some missing persons had property and assets to which their heirs were entitled. Widows could not remarry and orphans could not be adopted until the death of spouses or parents were confirmed.

In April 1950, the United Nations Convention on the Declaration of Death of Missing Persons established a procedure to obtain a declaration of death for missing persons.

This map of a grave in Michelbach an der Bilz (Baden-Württemberg) was drawn as part of the ITS’s post-war investigations of burial sites in occupied Germany. Investigations of gravesites helped reconstruct the history of the death marches. Notes on the map indicate the burial places of individuals with the surnames Seez, Bass, Nessyjwoda, Hrek, Semyschyn and a child named Krawtschück. There is also a mass grave identified in the centre. ITS Digital Archive 101099771. Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

Investigations relied on field operations, burial site searches, grave identifications, questioning of mayors, examination of hospital records and interviews with survivors in Displaced Persons camps. Based on these investigations, the ITS created maps showing the routes of the death marches, for example, this map detailing those from the Flossenbürg camp. Due to a lack of resources, the investigation ended in 1951. Evacuation Marches (IV-5-E), Arolsen Archives.

A clandestine photograph of prisoners marching to Dachau concentration camp on a death march. 26 April 1945. USHMM.

‘In the best interests of the child’

‘Six years in Germany is a long time in the life of a child, especially when he is taught to forget his past to learn new ways.’

M. Jean Henshaw. ‘UNRRA in the role of foster parent’, for The Zontian, October 1946.Tens of thousands of children became separated from their parents or orphaned by the end of the Second World War. Approximately 150,000 Jewish youth survived in liberated Europe.

Too young to decide

Among the children who found themselves alone (‘unaccompanied’) at war’s end were those who had survived concentration camps and children of foreign forced labourers. Parents searched for children who had been kidnapped by German authorities because they had been considered ‘racially suitable’ and ‘Germanised’.

The Child Search Branch was a special office of the International Tracing Service. It launched the Limited Registration Plan, a programme to check German foster homes, orphanages, hospitals and local records for missing children. Bereft parents submitted tracing requests, which the Child Tracing Section handled.

Through its field work, the ITS identified thousands of children who, in their opinion,belonged somewhere else, usually with their biological parents. The decision to remove a child from foster care was not easy and fraught with ethical and emotional challenges.

The wishes of the children did not always match those of their carers. Many children were too young to be able to tell aid workers who they were, or could no longer recall their lives before the war. Some had grown attached to their foster parents and did not wish to return to their biological families. Some children dreamed of joining the Bricha, the underground effort to help Jewish survivors escape post-war Europe for Mandate Palestine.

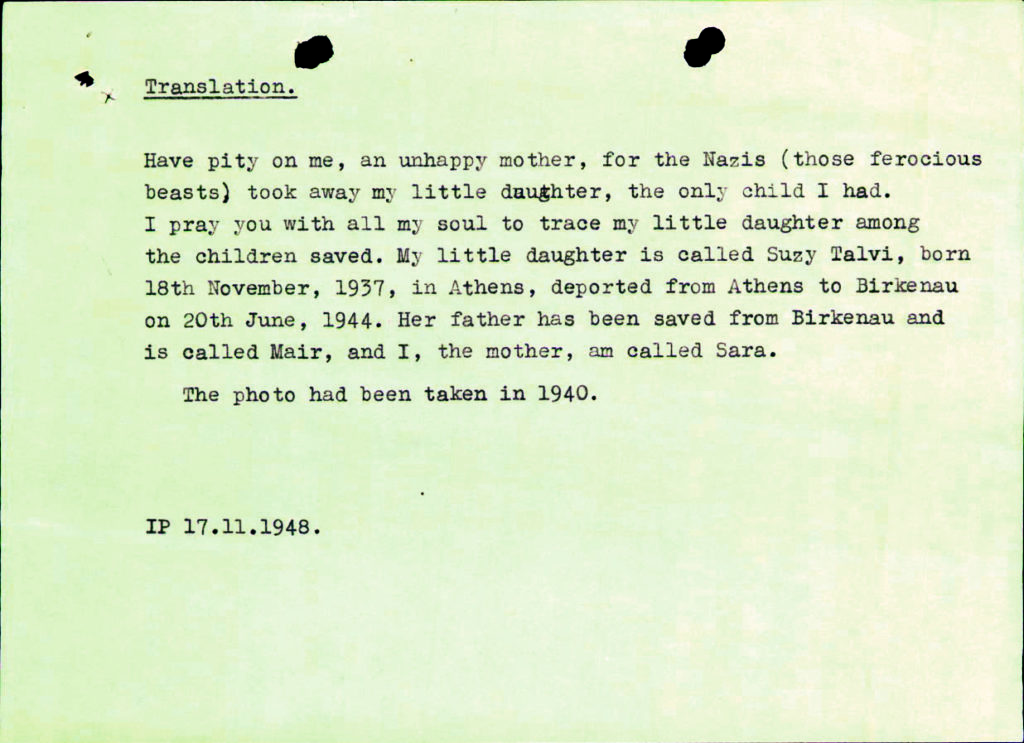

Sara and Suzy Talvi. Image taken in 1940. ITS Digital Archive.

On 17 November 1948, Sara Talvi wrote to the Tracing Bureau about ‘the only child’ she had. Her daughter, Suzy Talvi, was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau at the age of seven. Her case file was closed in December 1953. ITS Digital Archive 84594484/93/94. Wiener Holocaust Library.

In Focus: Ludwig Stein (Gasparik)

A Czech boy of 15, Ludwig described his harrowing experiences to relief workers after the war. His parents had both been interned in Buchenwald and died. He was desperate to emigrate to the United States where he had relatives.

Ludwig’s case file reveals his fragile emotional state. The relief workers found it difficult to care for him, and their resources were stretched. It turned out that Ludwig falsified his wartime story. He claimed to be Jewish so that he could get help to go to the United States. According to postwar testimony, Ludwig managed to get to Italy with IRO aid and then on to Palestine.

While children may have altered their biographical details to meet IRO rules, the majority of child cases were not fabricated. Ludwig Gasparik’s case reveals the psychological impact of war on children. It also shows the IRO review board’s complex, imperfect process of evaluation. The IRO’s determination of ‘eligibility’ often directed the fates of children.

Lázár Kleinman

© WL ITS Digital ArchiveIn Focus: Lázár Kleinman

Lázár Kleinman was born on 29 May 1929 in Ambud, a small village near Satu Mare, Romania, into an Orthodox Jewish family of eight children. After Hungary occupied Northern Transylvania in 1940, his family’s life was brutally upended. In 1944 his father was deported and he and his family were put into a ghetto. From there they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

After surviving several camps, Kleinman was found by the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) after the war and placed in the Kloster Indersdorf children’s home.

Mr Kleinman was recognised for his service to Holocaust education in the 2018 New Year’s Honours List. He spoke at the Library as part of it’s Fate Unknown exhibition series, where he talked about his experiences during the Holocaust, his story of survival, and learning about the fate of his family after the war. The recording of his talk is available below:

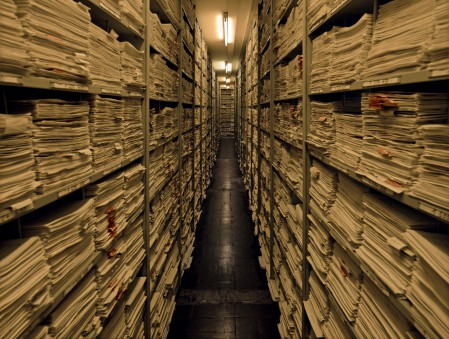

Tracing and Documentation files, ITS, Bad Arolsen.

© Richard Ehrlich for the US Holocaust Memorial MuseumLegacies of Fates Known and Unknown

The search for the millions of people who went missing after the Second World War continues today. Institutions such as The Wiener Library, the International Tracing Service (Germany), the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USA) and Yad Vashem (Israel) help people discover the fates of their relatives by navigating through documents and other traces of evidence left behind.

Documentary evidence of persecution, where it exists, assists with claims for compensation, stolen property and other assets. Yet scattered records around the world mean that a search can take months, years and decades.

In many cases, no relatives or descendants remained alive to carry on a search for the missing. Entire communities were destroyed.

These stories remain untold.

Searching at The Wiener Holocaust Library

The Wiener Holocaust Library helps visitors find information on the fates of their loved ones using the UK’s digital copy of the International Tracing Service (ITS) archive and other records in its collections. In rare cases, relatives are reunited or find descendants they never knew existed.

The ITS archive is vast. Yet it is only a fragment of the entire documentary record on the persecution of Jews and other victims during the Holocaust.

Find out more and learn how to begin your search at The Wiener Holocaust Library

How to access the ITS Archive at the WHL

-

Family Research Enquiries

Library staff will search the ITS free of charge for survivors, their families, and families of victims. Use this form to submit a research request.

Before submitting a request please see below for information on prioritising requests, turnaround time and your right to privacy.

-

Academic Enquiries

Library staff support scholars and students who wish to access the archive directly. If you are interested in carrying out academic research using the ITS let us know by submitting a research enquiry.

-

Online Access

Around 75-80% of the ITS archive is available online. Explore the online archive.

We recommend using the Arolsen Archives’ new online tool to help you decode the documents available in the online archive

-

Family Research Enquiries

Exhibition Catalogue

An exhibition catalogue featuring photographs and documents from our collections, case studies featured in the exhibition, and the history of the International Tracing Service archive is available to purchase via the Library’s online shop.

Acknowledgments

This exhibition was co-curated by Dr Christine Schmidt for The Wiener Library and Professor Dan Stone, Holocaust Research Institute, Royal Holloway, University of London, with extensive support from the International Tracing Service.

We are thankful for the support of the Royal Holloway Research Strategy Fund, the Leverhulme Trust, the German History Society, and the Library’s Friends and supporters, which make its work possible. With special thanks to Elise Bath and Dr Susanne Urban for their assistance.

Special thanks to Serena Dwerryhouse for the creation of this online exhibition.

Fate Unknown: The Search for the Missing After the Holocaust

Exhibition Type: Online Exhibition