This blog post was written by Elise Bath (Senior International Tracing Service Archive Researcher) and Roxzann Baker (The Holocaust Explained Project Coordinator) as part of Black History Month 2020.

Black and mixed-race people experienced persecution and discrimination before, during and after the Third Reich in Germany and elsewhere. Although Black people still face widespread racism across the world today, the number of researchers and historians who have explored the persecution of Black people under the Nazis in any meaningful depth remains relatively small.

This blog post aims to raise awareness of the persecution of Black and mixed-race people by the Nazis and their collaborators by exploring their incarceration in the Nazi camp system using records from the Library’s digital copy of the International Tracing Service archive.

Persecution

The persecution of Black and mixed-race people by the Nazi regime was complex and often contradictory, taking place at different times and being implemented in different ways across the German Reich. The Nazi Party believed that Black people were non-‘Aryan’ and racially inferior, and therefore a danger to the health of the German ‘Aryan’ population. Prior to the Nazi rise to power, it has been estimated that there were as many as 20,000 Black people living in Germany [Clarence Lusane, Hitler’s Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi Era, (New York: Routledge, 2002), 98]. During the Third Reich, the rights and living standards of these people were eroded by the Nazis.

As a result of persecutory Nazi legislation, many Black Germans and Black people living in Germany lost their jobs and careers, and had to resort to finding new work, or working illegally. Young Black and mixed-race people in Germany were also targeted by the Nazis’ education policy, with the introduction of race science as a compulsory subject in 1935, and the legal exclusion of Black and mixed-race children in schools across the whole of the Third Reich from 1941.

One of the most extreme pre-war actions taken against Black Germans by the Nazi authorities was the mass sterilisation of the Rhineland Children in 1937. The Rhineland Children were 600-800 children who had been born to white German women and Black French soldiers (who had occupied the Rhineland following Germany’s defeat in the First World War). In total, approximately 385 children were secretly sterilised, shortly before most of them reached adulthood.

Incarcaration

Some Black and mixed-race people were also imprisoned in concentration camps and forced labour camps during the Nazi era. Although, as the historians Robbie Aitken and Eve Rosenhaft explain: ‘the nominal grounds on which Blacks were held make it difficult to assess whether and under what circumstances someone could be arrested for simply being Black’ [Robbie Aitiken and Eve Rosenhaft, Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Disapora Community 1884-1960 (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 274] , some concentration camp records indicate that race was, at the very least, a significant contributing factor as to why people were incarcerated.

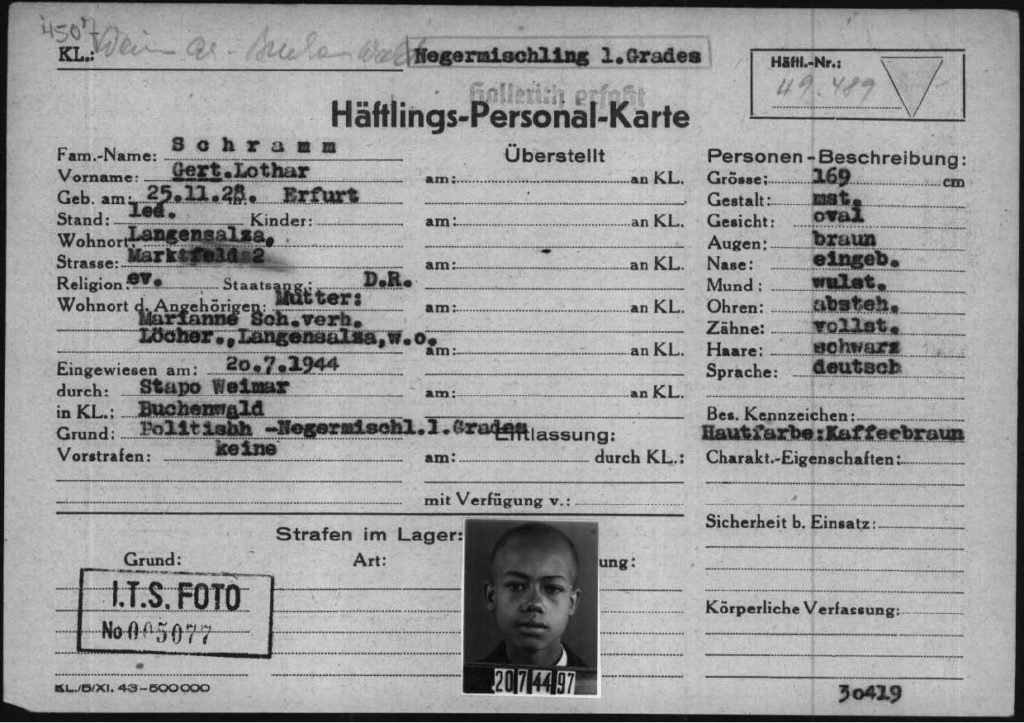

Gert Schramm, for example, was a mixed-race German man born in Erfurt on 25 November He was arrested on 6 May 1944 in Bad Langensalza and sent to Buchenwald concentration camp where he was given prisoner number 49489. The document below is Gert’s Prisoner Registration Card from that camp. As well as showing his basic biographical details and a physical description, this record also gives brief details of Gert’s arrest and arrival into Buchenwald. In the section of this document which gives the reason for arrest, two are given. The first is ‘politisch’ , i.e. political, and the second is ‘Negermischling 1. Grades,’ a racial slur used to indicate that a person was mixed-race. The fact that Gert’s ethnicity appears in the section of card used to record a reason for arrest indicates that this was a factor in his incarceration.

Courtesy of The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections, International Tracing Service Digital Archive, Document number 7058062#1

A number of Black people were among those arrested as part of ‘Aktion Meerschaum’ (‘Operation Seafoam’). The 1944 operation was carried out in western Europe by the Nazis and their collaborators. Real or suspected members of the resistance were rounded up and deported to various sites of detention where they were held under especially close supervision, and under no circumstances released or allowed to escape. Raphael Elizé, for example, was French veterinarian born on 4 February 1891 in Le Lamentin in Martinique. He was arrested as part of Operation Seafoam in Paris in January 1944 and deported to Buchenwald. He was killed there by an Allied bombing raid just over a year later, in February 1945. Baba Diallo, born on 26 November 1913 in Segou, Mali, was another French national deported to Buchenwald in January 1944 as part of Operation Seafoam. Baba died there on 11 October 1944. Both of these men have ‘Meerschaum’ written at the top of their Prisoner Registration Cards:

There are further documentary traces of Black and mixed-race people throughout the Nazi camp system. Erika Ngando and Martha Borck, née Ndumbe, both German-born of Cameroonian descent, were incarcerated in Ravensbrück camp. Josefa van de Want, nee Boholla, and her white husband were both incarcerated in Stutthof on charges of listening to enemy broadcasts. Dominique Mendy, Ernest Armand Huss, Sidi Camara, and Isidor Alpha, all Frenchmen of colour, were deported together to Neuengamme concentration camp, arriving there on 24 May 1944.

End of war

Although most Black people living in Germany survived the Third Reich, they were subjected to substantial persecution, discrimination and deteriorating living conditions throughout the Nazi era. The racist discrimination and persecution that they faced under the Nazis continued after the conclusion of the Second World War in many countries around the world. The insidious nature of this racism can be seen in post-war comments made by a United Nations official about a survivor of Nazi persecution named Theodor Michael. Theodor was a Black American who had been working in Europe, when he was caught up in Nazi persection. He survived, and submitted an application for financial assistance in the immediate post-war period, hoping to leave Germany and the Displaced Persons Camps in which he was living. In a section at the bottom of the report entitled ‘Interviewers’ recommendations,’ the official writes, ‘Eligibility to be reviewed! Being a Negro, will any country accept him?’.

In 1961, the Library’s founder Alfred Wiener wrote in the Jewish Chronicle that

“It is no good to isolate antisemitism from all other forms of intolerance and hatred in human relations, and that one cannot successfully combat anti-Jewish prejudice while ignoring the colour bar or other manifestations of racialism”.

In the Library today we pay attention not only to antisemitism and Nazism but to fascist and racialist movements as well”. Events in 2020, including the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the reactions to those murders, show that this racism is still very much alive and present within our societies today. The Wiener Holocaust Library stands against racism of all forms, and recognises the discrimination that Black people continue to face.

Recommend reading:

- Robbie Aitiken and Eve Rosenhaft, Black Germany: The Making and Unmaking of a Disapora Community 1884-1960 (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Clarence Lusane, Hitler’s Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of Afro-Germans, European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi-Era, (New York: Routledge, 2002).

- Tina Campt, Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender, and Memory in the Third Reich, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2004).

- Theodor Michael, Black German: An Afro-German Life in the Twentieth Century, translated by Eve Rosenhaft, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017).

For more related sources, try a search for any of the following keywords in our Collections Catalogue: Black history; Racial discrimination; Racial doctrine; Sterilisation; Personal narratives and Resistance.

3 comments so far

watched a movie about this subject why isn’t this in most library’s or more commonly known

Why isn’t this common knowledge ?

the official documents and writes about an American Black man displaced in Germany,

‘Eligibility to be reviewed! Being a Negro, will any country accept him?’.

This is SHOCKING, why is this history NOT better known? Where are the books films…studies???